Latin American Artists and Race

Our new book traces the racial mix and more through artists’ eyes in this vibrant, culturally diverse continent

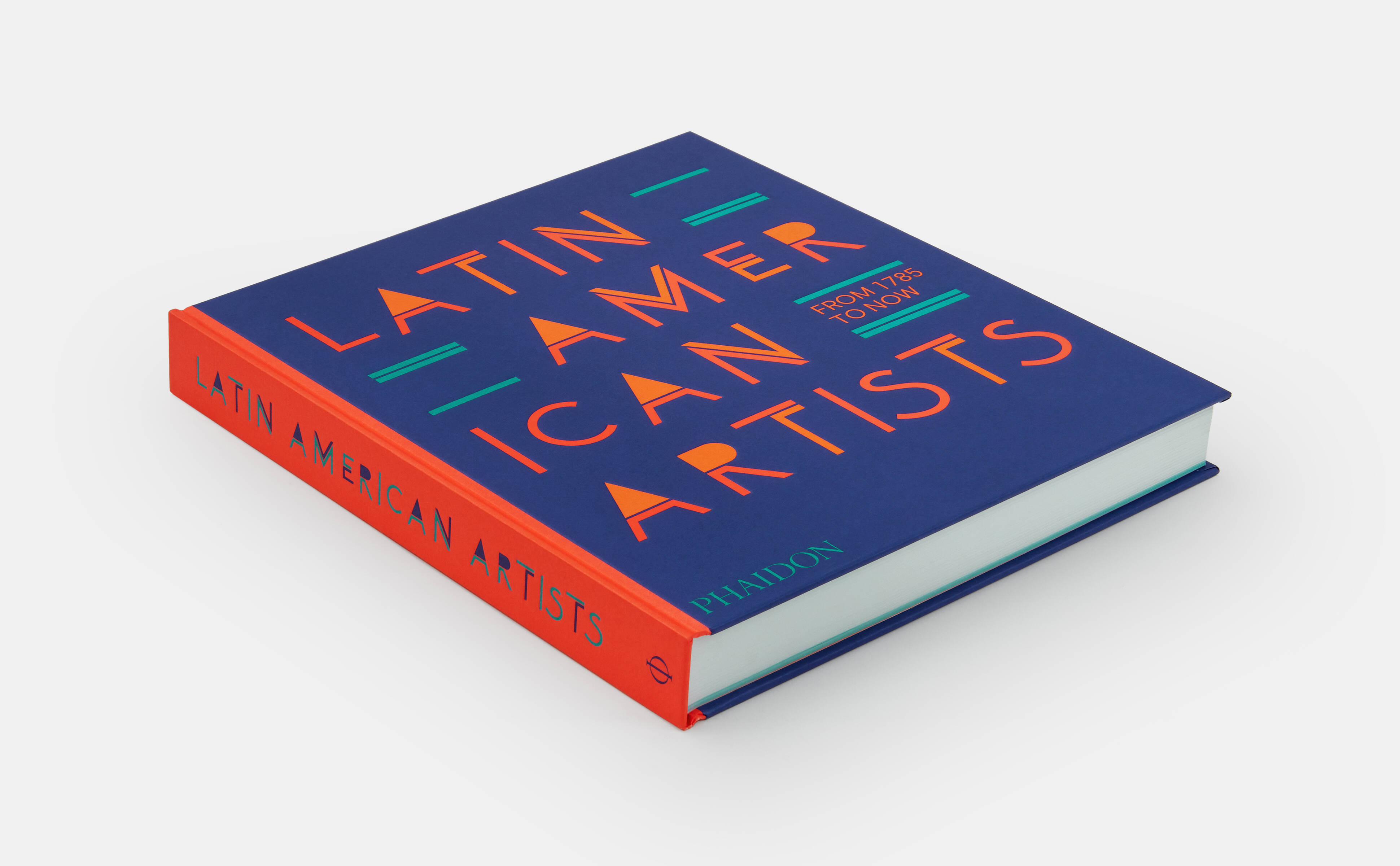

We may think of North America as the great melting pot, but Latinate nations south of the border can lay claim to an equal level of diversity, with Imperial conquest, the slave trade and later waves of migration diversifying their racial make-up. Just take a look at Latin American Artists: From 1785 to Now for some of the ways in which this has affected and informed artists from the region.

Presented in a wonderfully simple A-Z format, the book reproduces key works by 308 artists who were born, or who have lived, in the 20 Spanish and Portuguese-speaking regions of Latin America.

Nature, art, money, and power all shape and feature in many of the paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, video stills, and installations shown in this book, as does the role of ethnicity and race.

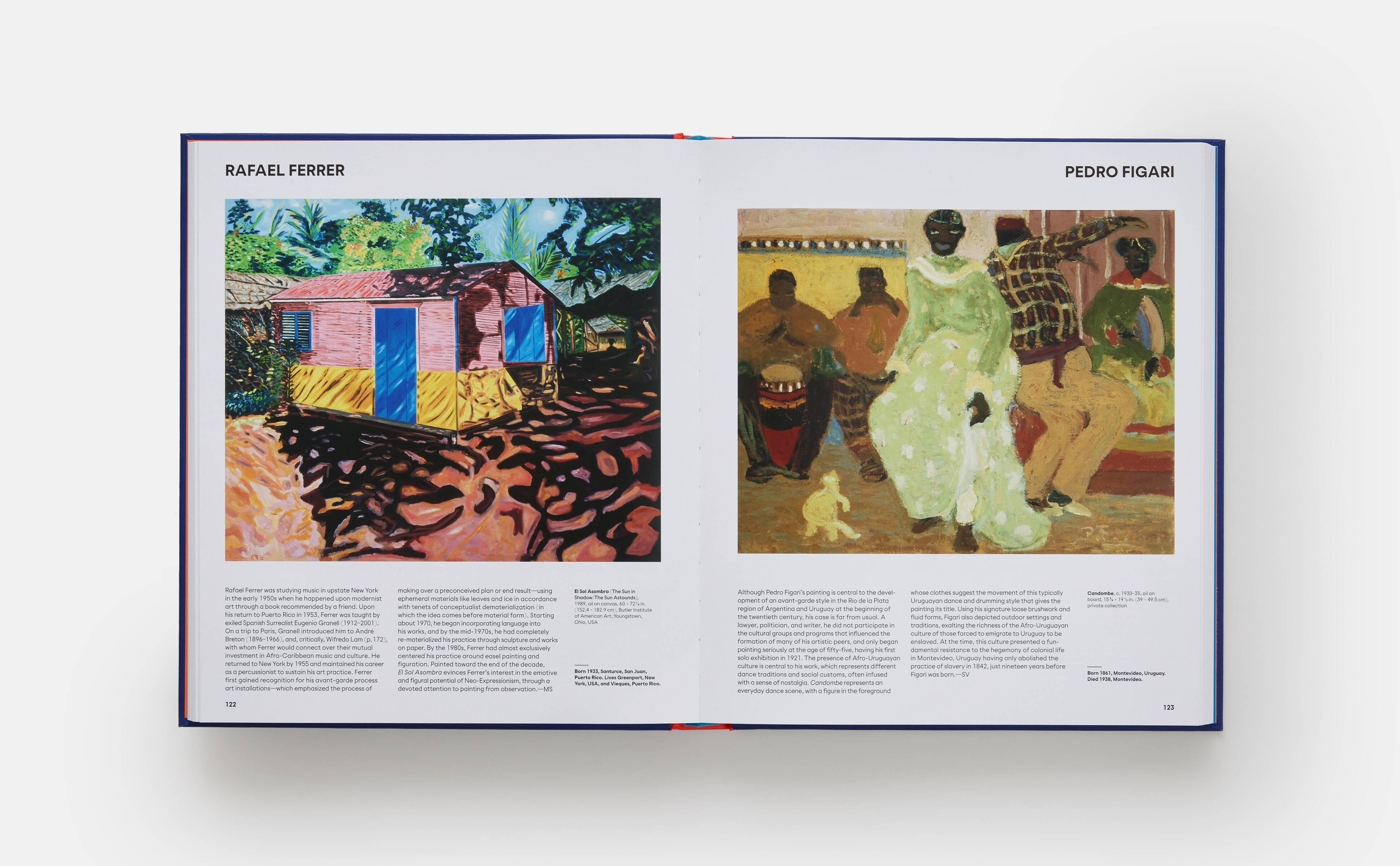

For proud, defiant 20th century depictions, take a look at the work of the Uruguayan painter Pedro Figari. “A lawyer, politician, and writer, he did not participate in the cultural groups and programs that influenced the formation of many of his artistic peers, and only began painting seriously at the age of fifty-five, having his first solo exhibition in 1921,” the book explains.

“The presence of Afro-Uruguayan culture is central to his work, which represents different dance traditions and social customs, often infused with a sense of nostalgia. Candombe (spread pictured) represents an everyday dance scene, with a figure in the foreground whose clothes suggest the movement of this typically Uruguayan dance and drumming style that gives the painting its title.”

Using his signature loose brushwork and fluid forms, Figari also depicted outdoor settings and traditions, exalting the richness of the Afro-Uruguayan culture of those forced to emigrate to Uruguay to be enslaved. “At the time, this culture presented a fundamental resistance to the hegemony of colonial life in Montevideo, Uruguay having only abolished the practice of slavery in 1842, just nineteen years before Figari was born.”

For a more nuanced, sombre take from more recent times, turn to the page on Dalton Paula, whose work centres on Afro-Brazilian myth and ritual. “In his painted portraits, people are transformed into imagined beings and deities that mix with mortals in a celebration of religious syncretism, faith, tradition, and popular culture,” explains the new book. “His project addresses the historical suppression of Black Indigeneity in the visual record of Brazilian culture, aiming to accord a new sense of autonomy to his cast of characters.

“Drawn from a combination of historical references and contemporary local photographs, his protagonists occupy their place in this world, an assertion of Indigenous pride through a painterly process based in a studied use of color, texture, and rhythm. Exalting the human body and its expressions, Paula concentrates his compositions on the head and shoulders, frequently adorning the hair of his subjects with 22-carat gold leaf as seen in the braids worn by the woman in Chica da Silva. Dressed in nineteenth-century clothing, she gazes silently at the viewer, an air of saudade (melancholy) in her eyes, as though waiting for someone or something that will never materialise.”

To find out more about both these artists and many more, get a copy of Latin American Artists: From 1785 to Now, here.