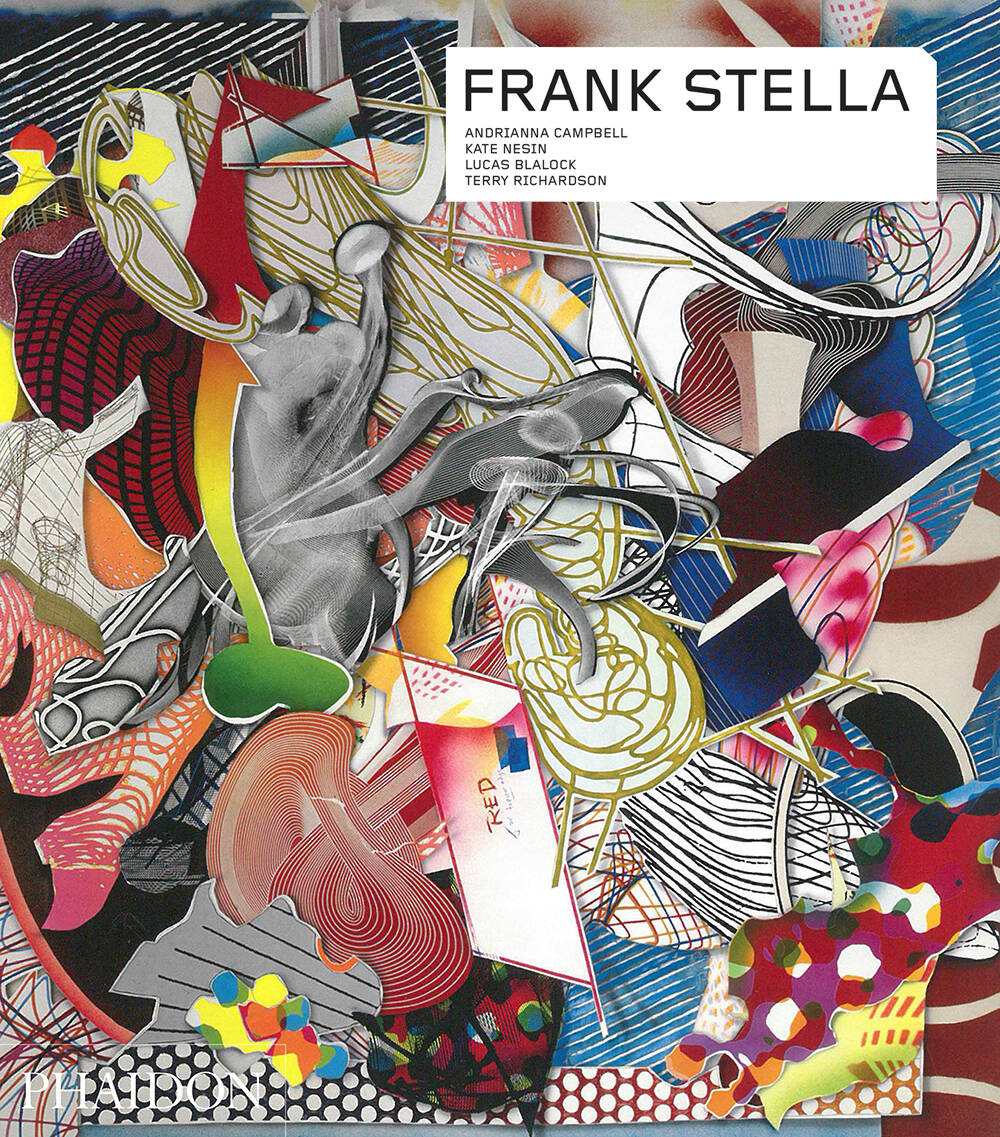

Frank Stella - 1936-2024

We pay homage to the groundbreaking artist who has died aged 88.

Frank Stella, an artist whose groundbreaking work redefined the boundaries of abstraction and minimalism, passed away on May 4, 2024, at the age of 88.

Over a career that spanned more than six decades, Stella’s innovative approaches and relentless exploration of form and colour left an indelible mark on the art world. His legacy is celebrated through his prolific output, influential theories, and his profound impact on both contemporary and future generations of artists.

“Stella’s work is so knowingly, joyfully unrestrained – stretching or transgressing boundary after boundary, between categories of media, between studio and factory, between good and bad taste,” writes Kate Nesin in our Contemporary Artist Series book on the artist.

Frank Stella, Empress of India, 1965, metallic powder in polymer

emulsion paint on canvas, 200 x 570 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frank Stella, Empress of India, 1965, metallic powder in polymer

emulsion paint on canvas, 200 x 570 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Born on May 12, 1936, in Malden, Massachusetts, Frank Philip Stella exhibited an early interest in art, which he pursued through his education at Phillips Academy in Andover and later at Princeton University, where he studied history. Stella's initial artistic inspirations were the works of abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline, but it was his move to New York City in the late 1950s that catalysed his unique voice in the art world. Stella rapidly became a central figure in the city's vibrant art scene.

His early work was characterized by the Black Paintings, a series of stark, black striped canvases that rejected the gestural intensity of abstract expressionism in favour of a cooler, more detached formalism.

"What you see is what you see," Stella famously declared during a conversation with Donald Judd, encapsulating his belief in the visual experience of art over symbolic or narrative interpretations. This mantra not only guided his own work but also influenced a generation of artists seeking to strip art down to its essentials.

As Kate Nesin writes in the CAS book on him. “Stella’s first striped paintings were and often still are claimed as ‘literalist’, ready precursors to the Minimalist work that constituted abstraction’s primary avant-garde during the early and mid-1960s: spare, geometric, serial or modular, works transparent in their fabrication and often industrial in their finish, works that blur or ignore conventional boundaries between painting and sculpture. Many then and since have acknowledged the young Stella as Minimalism’s ‘father’.

Frank Stella, Organdie, 1997, acrylic on canvas, 396 × 396 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frank Stella, Organdie, 1997, acrylic on canvas, 396 × 396 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In parallel, his striped canvases were and still are claimed as high modernist, certainly the modernism espoused primarily by mid-century critic Clement Greenberg, whom Stella had read with admiration in college.”

But Stella was never content to stand still. Michele Robecchi, Phaidon’s Commissioning editor for art, who commissioned and worked closely with the artist on his Contemporary Artist Series book said:

“I was deeply impressed and honoured when he accepted my invitation to work on a CAS book. Marianne Boesky made the introductions. You might think of Stella as the kind of artist who had outgrown that format, but he was always busy trying to reinvent himself. He wasn’t interested in his legacy. He was very much about being in the present tense.”

Robecchi’s thoughts are mirrored by Stella himself, who in the CAS book told interviewer Andrianna Campbell: “With Minimalism, I was there, but I’m not there now, except in a literal way: in the paintings that are extant from then. When you see them, you can say, ‘Oh, that’s from the 1960s.’

“But the 1960s didn’t live on, and so I think it doesn’t have any real resonance anymore, except in the work that’s made to look like art, but isn’t art. I didn’t want my work to live on continuously as a conversation or product of the 1960s, the product of who I was as a very young artist.”

Frank Stella, Scarlatti K series: K.432, 2013, painted ABS RTP and metal, 150 x 142 x 132 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Instead, Stella produced thousands of individual works across six decades, divided among more than sixty series and categorized variously (sometimes conflictingly) as paintings, prints, reliefs and sculptures; using commercial and industrial paints, canvas, paper, print media, wood, felt, cardboard, aluminium, magnesium, steel, bronze, ceramic, fibreglass, carbon fibre, foam, bamboo, numerous plastics and Corian; brushing, spraying, collaging, machine-cutting, casting, assembling, machine-carving, as well as 3-D printing and laser sintering, among other forms of rapid prototyping.

Frank Stella, Scarlatti K series: K.432, 2013, painted ABS RTP and metal, 150 x 142 x 132 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Instead, Stella produced thousands of individual works across six decades, divided among more than sixty series and categorized variously (sometimes conflictingly) as paintings, prints, reliefs and sculptures; using commercial and industrial paints, canvas, paper, print media, wood, felt, cardboard, aluminium, magnesium, steel, bronze, ceramic, fibreglass, carbon fibre, foam, bamboo, numerous plastics and Corian; brushing, spraying, collaging, machine-cutting, casting, assembling, machine-carving, as well as 3-D printing and laser sintering, among other forms of rapid prototyping.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Stella continued to innovate. His series of shaped canvases, such as the Irregular Polygons and Protractor series, broke free from the traditional rectangular format and introduced vibrant colours and geometric forms. These works were celebrated for their dynamic compositions and bold use of colour, redefining the possibilities of abstract painting.

"I wasn’t like others in the 1960s,” he tells Campbell in the CAS book. “It wasn’t geometry that interested me; that was a means to an end. The thing about geometry is that you need it to measure and to be able to build things. Geometry is just part of measuring and building surfaces. You paint on surfaces, basically, and if you don’t paint on surfaces, or if you take a surface for granted, then you’re creating surfaces, or painting on top of the surfaces you create. It’s the basic ingredient for making paintings or art.”

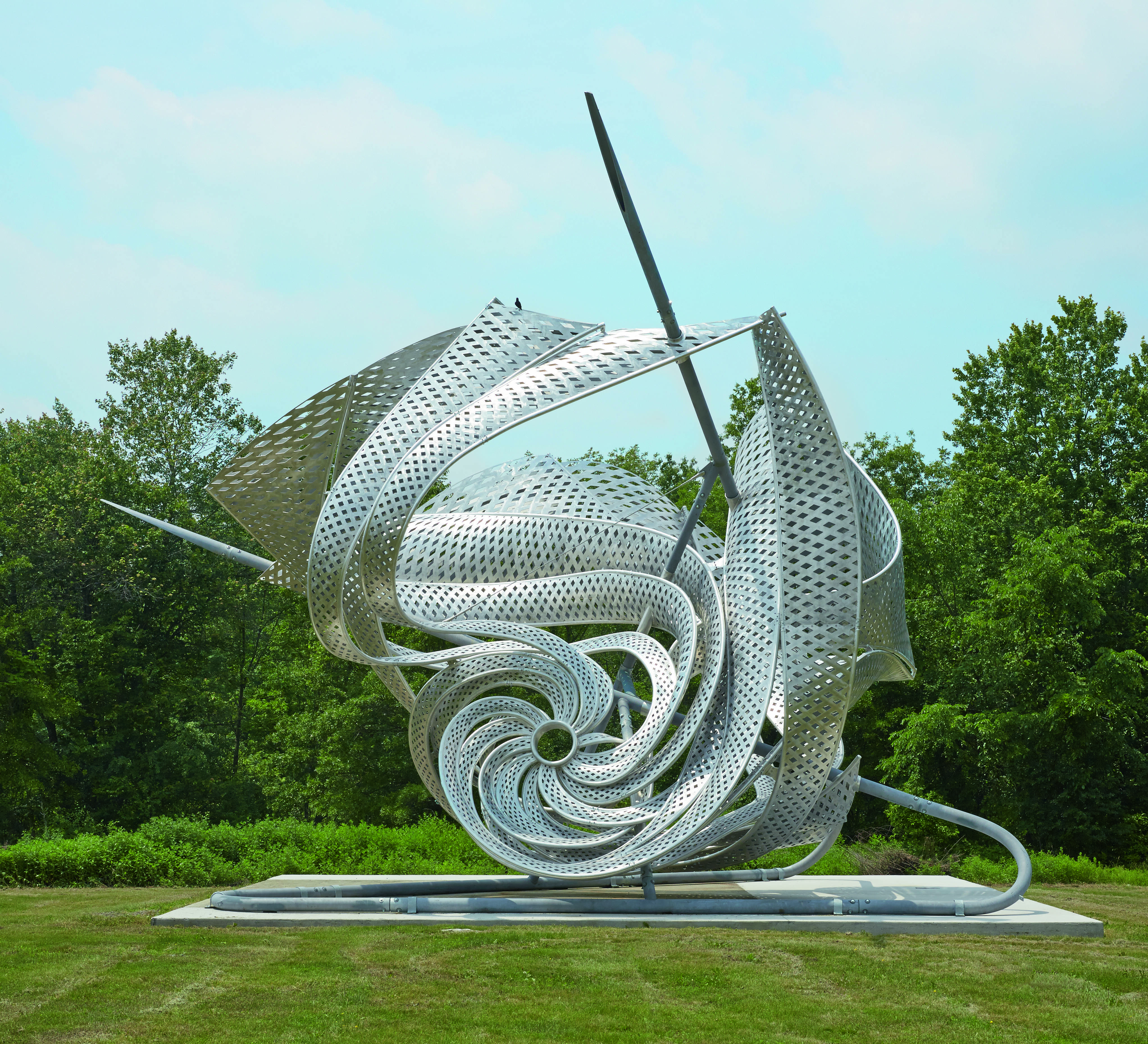

In the 1980s, Stella embarked on a series of increasingly complex works that incorporated elements of relief and three-dimensionality, blurring the lines between painting and sculpture. His Moby-Dick series are notable examples, where the works expanded into the viewer’s space, inviting a more immersive interaction.

Michele Robecchi remembers approaching his studio in Upstate New York for the first time.

“It was in a fairly remote location but you could see from miles away that this was where Stella was. There were huge sculptures everywhere – in the front lawn, the back garden. He was always making work whether someone was going to show it or not.

“He had welders and carpenters around him - all technical people. He didn’t like the idea of having aspiring artists as studio assistants. He wanted to realise his vision with no other creative input whatsoever. Occasionally he would pretend not to hear if he didn’t want to hear something, even though he could hear perfectly well!”

Frank Stella, K.304, 2013, aluminum and stainless steel, 920 x 1270 x 1170 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frank Stella, K.304, 2013, aluminum and stainless steel, 920 x 1270 x 1170 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Stella’s commitment to pushing the boundaries of art extended beyond his own practice. He was an eloquent advocate for the importance of art in society, often speaking about the transformative power of creativity. In addition to his studio work, he was also a teacher and mentor, albeit a somewhat reluctant and often bruisingly honest one.

“I’ve taught a little, but mostly only for a semester at a time. I don’t think I was a very good teacher,” he says in the book.

“When I taught, it was as if I was being asked to teach artists how to do marketing. Marketing hurts students. Schools are just stealing their money. Then they repeat the saying to someone else and then you have another generation that think about marketing more than art.”

“When I was teaching at Cooper Union, I’d enjoy two hours in a history class, then I’d go to the MFA studios, and they’d want a playbook on how to be successful. I said ‘You know, you’re in graduate school. This is the time for you to really focus on the work and on making the work better. Bring it to a place where you’re happy.”

Stella’s own work garnered numerous accolades throughout his life. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 2009 and received honorary degrees from multiple institutions. His works are held in major collections around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Each piece stands as a testament to his innovative spirit and enduring influence.

“Sadly he never had a proper institutional show in Italy,” Robecchi remembers. “When we met, we talked a bit about his Italian roots and I know that he would have loved that. We also connected over his love for racing cars. He actually had one of Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari Formula One cars in his studio. He had swapped some art for the car.”

Frank Stella, Atalanta and Hippomenes, 2017, painted metal, Pu-foam, Fibreglass, 351 x 409 x 237 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Frank Stella, Atalanta and Hippomenes, 2017, painted metal, Pu-foam, Fibreglass, 351 x 409 x 237 cm. Picture credit: © Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Despite his success, Stella remained grounded and focused on the continual evolution of his practice. "I don't think of my work as a career; it's more of a lifetime project," he once remarked. This lifelong commitment to his art was evident in his relentless experimentation and refusal to be confined by any single style or movement.

As he said in his CAS book “In the end it’s all the same. You have to make it look all right.”