Nick Waplington tells us how he got this photograph which is now a Phaidon limited edition

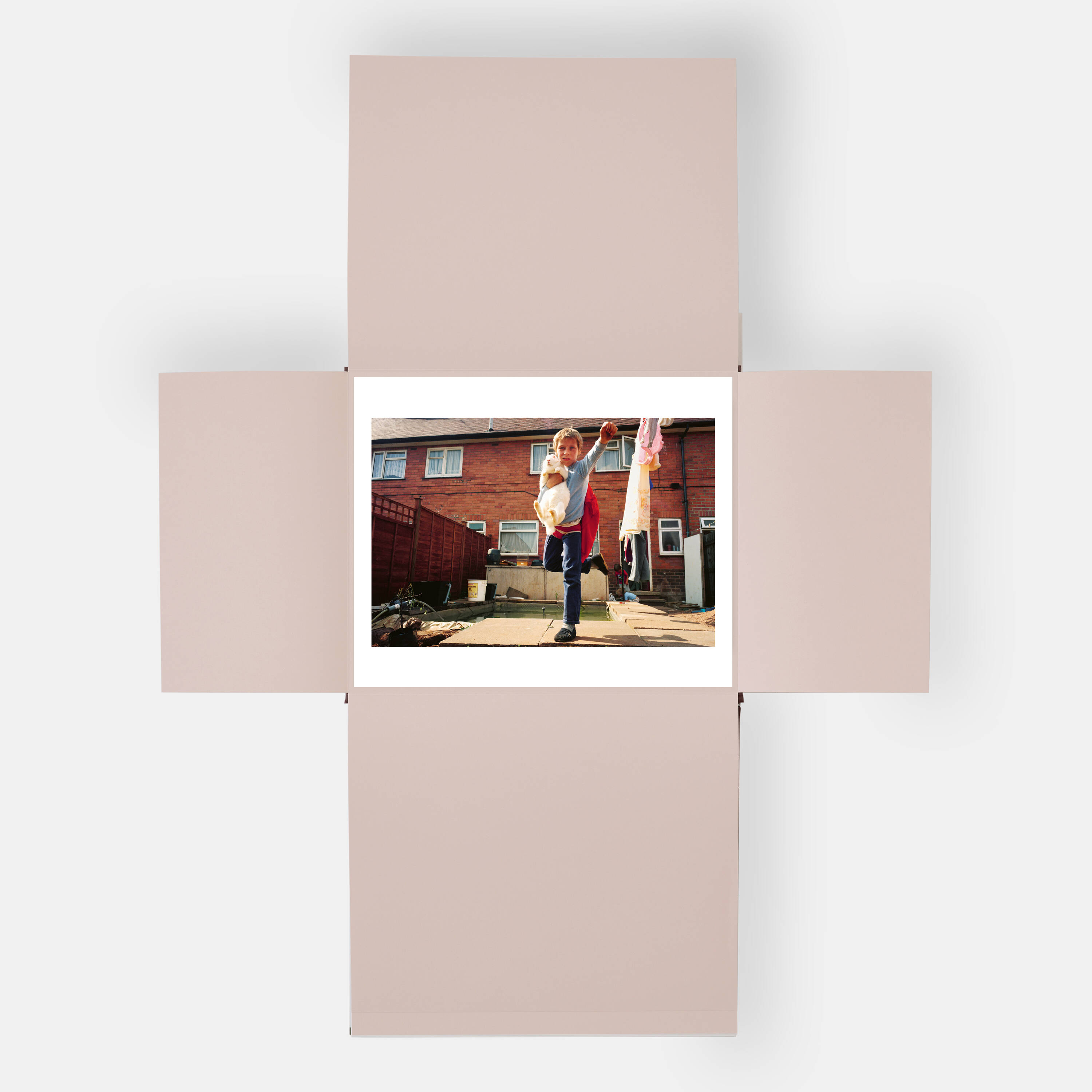

Untitled (Superman and Rabbit), 1989 (2023) was part of the esteemed photographer's highly acclaimed Living Room project

For more than four decades now, the London- and New York-based artist Nick Waplington has used photography to capture the complex and far-reaching aspects of our lived experience.

He rose to prominence in the early 1990s with Living Room, a series portraying working-class domestic life in Nottingham, England, 100 miles north-west of London, and has since become known for his unfiltered, unflinching depictions of people and places, and the socio-political backgrounds that define them.

The surreal, hypnotic nature of Waplington’s large-format landscapes is always to the fore. From the hedonism and excess that permeate his images of 90’s New York club culture at the Sound Factory, Save The Robots, and The Limelight; through the chaos, violence and euphoria depicted in riots, protests and free parties; to the ethereal late-summer scenes of swimmers on East London’s River Lea, Waplington’s work transcends stereotypes.

However, it was his Living Room series of photographs, taken on the large inter-war-built Broxtowe council estate in Nottingham, where most residents worked in the coal mines, that were to prove a turning point in his career.

Waplington spent months documenting life on the estate, gaining the trust of residents and spending time with families, helping them with daily chores, playing with the children, even sitting down to lunch and dinner with them.

The resulting body of work was an artistic success. The exhibition toured the US and Waplington was given a show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

His subsequent work has encompassed many stylistic shifts - In 2015 he became the first British photographer to have a one-person exhibition in the main exhibition space at Tate Britain in London with his Alexander McQueen photo project, Working Process - but the photographs in his Living Room Series are, to this day, hailed for their emotional impact and intimacy.

Amazingly, Waplington has never made an edition from this series of pictures. Until now. Untitled (Superman and Rabbit), 1989 (2023) is a limited edition image of the son of a family Waplington befriended on the estate.

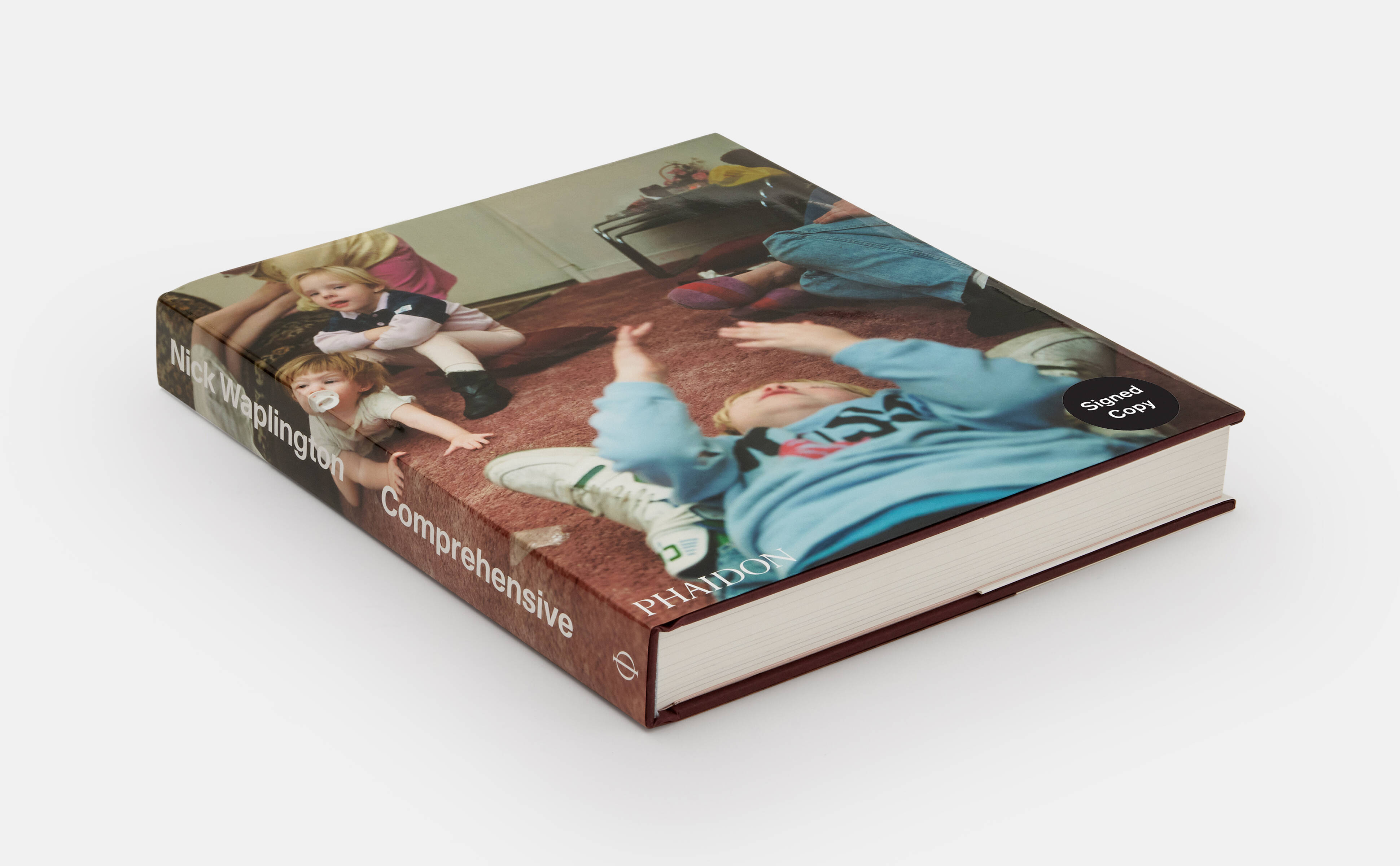

The C-Type print measures 282 x 232 mm (11 x 9 in) sheet size: 257 x 170 mm (10 x 6 2/3 in) image size, and comes in an edition of 50 plus 12 APs Signed and numbered by the artist. This limited edition print comes with a signed copy of Nick Waplington: Comprehensive, the most extensive survey to date on the prolific British photographer and artist and his body of work.

Here, he tells us about the circumstances behind the photograph, he looks back on the Living Room series of photographs from which it is taken, and reflects on how his own violent childhood ultimately may have proved inspirational in his work.

Nick Waplington with Tracey Emin at the Phaidon 100th anniversary party at Christie's London, October 2023 - photo by Karen Hatch

Nick Waplington with Tracey Emin at the Phaidon 100th anniversary party at Christie's London, October 2023 - photo by Karen Hatch

How did the project come about? “The pictures were taken very slowly over many years. I didn’t ever give myself any deadlines. When I met people who worked to deadline, that kind of struck me as being more like journalism.”

“My intention from the start really was to make a photo book; and that was going to take as long as it needed to take. I wasn’t really bothered. I just thought I would have to work at Pork Farms (a Nottingham-based producer and distributor of pork-based bakery products) making pork pies during the week and take pictures at the weekend for as long as I needed to do it.”

What was your approach at the time? “When I thought something was going to happen I’d pick up the camera and take some pictures very quickly and then put the camera down. And then not take any again for a while. You don’t want to be taking pictures all the time in a documentary-esque situation, because otherwise it becomes about you and the camera and not the situation. It’s about having an instinct for when something is going to happen.”

So the actual picture taking was almost not paramount? “Yes. To have a kind of general involvement in the activities that were happening on the estate was paramount. I would play football with the kids. I was just generally ‘around’. People don’t realise the complex lighting system in those pictures. That was the ‘set-up’ but the ratio of time to pictures taken was very small.”

“I’d go out on Saturday night and go to the Garage in Nottingham and hear Graeme Park deejay – this was before he was at the Haçienda. Then I’d go back to my grandad’s and go back round there on Sunday. Have Sunday lunch, watch the football – the family were Notts County fans - and play with the kids until seven or eight in the evening, every weekend. That was my routine.”

What do you remember about taking the image that is now the edition? “I’d rather not say the boy’s name, but he would do that dressing up periodically. I actually asked him to do it that Sunday. It was the winter, but it was a clear sunny day. So it was freezing cold for him, but we went outside.”

If ever a rabbit could look terrified, this one does. “That albino rabbit was really big, enormous. They had a lot of pets. A lot of carp, and rabbits, and gerbils, and rats. I would often spend my Sundays with that family.”

“I don’t know what happened to the boy. The family moved away to Bedfordshire, and I lost contact with them. They were very nice. They were very Christian. I used to go to church with them.”

“Then the parents split up and the mother moved to Bedford with the four children. I helped them move actually. I knew where they were but then lost contact with them. I would like to find them.”

At the time, the writer and critic John Berger compared the pictures to baroque painting. . . “Yes, which was perceptive. And there was a really good write up of the show at Aperture in Artforum. I got a show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art out of it a couple of years later. But, at the time, most people didn’t know what to make of it.”

“The people who knew about photography liked the pictures, but the traditionalists didn’t like them. It tended to be more people in the art world who were more open to new ways of working who liked the work.”

Do you think the necessity to become ‘the quiet child’ in your stepfather’s presence may have helped in some way with your later ‘embedded’ approach to your photographic projects?

“My childhood with my stepfather was about not being allowed to speak unless I was spoken to. And, if I did, the situation would become pretty brutal. So I think not being able to talk did lead me to spending a lot of time observing and memorising things, yes.”

“Also I’m left-handed and dyslexic and I believe that you see things in a different way to people who are kind of regular-handed.”

“I can memorise scenes and landscapes. I’m also very attuned to changes in the situation of people around me, because I had to be aware of minute changes as a child, because it was a situation of fear all the time during my childhood.”

“I was constantly in fear. Only when he was away on business could I relax. Luckily he went away a lot. But when he was there, or when he came in that was it. You had to be aware that things could be volatile and could go wrong. Living with that fear is something I didn’t really think about until I was much older.”

“Actually, it really helped me a lot when I was working with (the late fashion designer) Alexander McQueen. That was a year-long process, and I told him and his staff to not talk to me at all. I was just not there. It was funny, after his show a year later, when they all came to his room in the hotel, and I was also there, it was the first time I actually spoke to them.”

“It was also a good moment because it was the year before smartphones, so nobody was just sitting there on their screens. That kind of project would be hard to do now.”

When shooting the Living Room project did you feel you had to like, or perhaps be liked, by the people involved for it to work?

“I liked some of the people. Obviously there were people on the estate who were not very likeable. Actually I made two books - the ‘80s pictures and the ‘90s pictures. And there was a kind of a switch between the two.”

“The difference between the two was the arrival of Class A drugs. That changed the dynamic of the pictures, the nature of the work. The Class A drugs weren’t really there in the 80s. By the time you got to the early 90s they had reached the estate where I was working. Not that any of the people in my pictures participated in that – they didn’t – but it was around, and therefore there was a change of atmosphere.”

Did you think you learned any lasting life lessons from the close quarters work you typically engaged in? “I don’t know what I’ve learned, other than from a general left wing point of view. I haven’t been very careerist. I don’t have a YouTube channel; I’m not constantly plugging myself. As long as I’ve got enough money to continue I’m fine.”

“If I had been pushier I would have been better known. Not that I think it matters in the extended long term because the work has a life of its own; but personally, I’ve had a life where I’ve just done what I want to do every day.”

Buy Untitled (Superman and Rabbit), 1989 (2023) here.